Having commenced in 2011, the survey is the longest running survey of its type and one of the most comprehensive longitudinal data sets of school leader health and wellbeing in the world.

Co-lead investigator Professor Herb Marsh, who’s been at the helm of the report since 2016, says increasing job demands and burnout are putting school principals at risk.

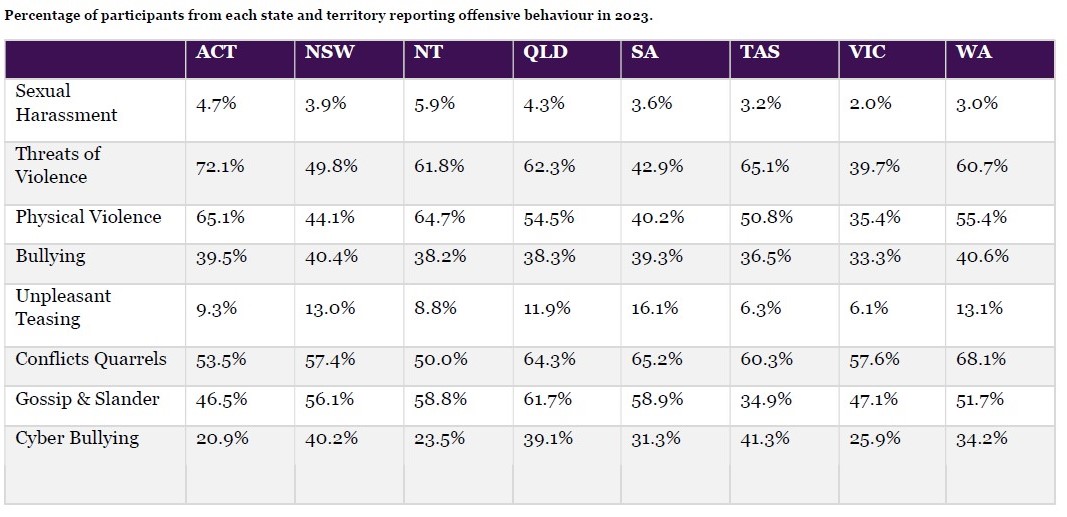

“It is deeply concerning that offensive behaviour towards school leaders and teachers persists and appears to be on the rise,” he says.

However, despite the spike in violence and the toll on their mental health and wellbeing, the survey also found school leaders are showing surprisingly strong levels of resilience, and their work commitment remains high.

Co-lead investigator and leading school wellbeing expert Associate Professor Theresa Dicke says that resilience has increased ever so slightly since it was first included in the survey in 2017, and that’s important, because the higher levels of resilience a principal reports, the less likely that principal is to say that they are considering leaving their current job.

“This demonstrates the important role that resilience plays in preventing work-related strain in school leaders,” Dicke, who works in the ACU’s Institute for Positive Psychology and Education (IPPE), says.

“We also report on job satisfaction, meaning of work and commitment to the workplace, and they’re also quite high, which is a very interesting phenomenon to see in school leaders.

“So it’s almost like a paradox, that we see that our school leaders show very high levels of burnout, sleeping troubles, etc, so more negative scales, but they also show incredibly high level of these positive scales, compared to the general population.”

Dicke says it goes to show how much we should appreciate our school leaders and the strength that they are bringing in, and that they draw on, in order to do their jobs.

“And we can see it in the comments, too,” she explains.

“So in the open-ended comments principals will report that they love their job, and they love what they’re doing – but sometimes they’re just too exhausted to continue doing it, so it’s this internal struggle.”

In the 2023 survey of 2300 principals, the five main sources of stress reported included the sheer quantity of work, lack of time to focus on teaching and learning, mental health of students, mental health of staff, and student-related issues.

One in five school leaders reported moderate to severe depression, with early career school leaders showing greater levels of anxiety, while others, the survey indicated, are at risk of serious mental health concerns, including burnout, stress, and difficulty sleeping.

Alarmingly, 42.6 per cent of school principals triggered a “red flag” email in 2023, signalling risk of self-harm, occupational health problems, or serious impact on their quality of life.

The survey indicates that more than half of school principals intend to quit or retire early, with experienced school leaders (those with more than 15 years behind them) leading the charge to leave.

There is also concern about mid-career leaders turning their backs on long-term principalship, with almost 60 per cent of those with six to 10 years’ experience wanting to leave the profession.

More than half of principals (53.9 per cent) reported experiencing threats of violence, nearly half (48.2 per cent) reported physical violence, up from 44.0 per cent last year, while of those reporting physical violence, a staggering 96.3 per cent was at the hands of students.

Threats of violence from parents/caregivers has remained high in 2023 at 65.6 per cent.

Dicke says there are two things to keep in mind when interpreting the highest reported levels of physical violence, threats of violence and bullying of school leaders in the survey’s 13-year history.

“So firstly, it doesn’t always mean that the principal was, for example, punched in the face, it could also mean, that the principal had to resolve a brawl or something similar in the playground – so that needs to be taken into account.

“And also, in today’s environment, there also might just be more awareness about violence and violent incidents. So while in the past, they didn’t think twice, now they are very aware about these inappropriate behaviours.”

Dicke is not convinced that this is a schools-specific phenomenon, but rather is actually a broader societal issue.

“We’re currently speaking to researchers in other 'helping' professions – so any profession that involves a service role, or a caring role for other people, such as psychologists, teachers, nurses, aged care workers, etc – and in talking to these researchers, we see very similar trends,” she says.

“This doesn’t diminish the problem, but instead, it shows that we need to look at this problem in a more systemic way and in how we function as a society, because obviously it’s a big issue, and violence is never OK, but these are the professions that are looking after our most vulnerable members in society – the youngest, the sick, and the oldest – and they are subjected to these high levels of violence.”

Addressing inappropriate behaviour from parents/caregivers to maintain a safe and conducive learning environment is one of the key recommendations from the report.

The Victorian School Community Safety Order, Dicke says, is an excellent start.

“The Victorian Government is working closely with us in evaluating that policy,” Dicke says.

“Queensland has also implemented its ‘Hostile people on the premises wilful disturbance and trespass procedure’, while the Northern Territory has the ‘Trespass on school grounds procedures’.

“This is great and commendable that these have been implemented, but what’s important is are they working? Are they doing what they’re supposed to be doing? And that’s a great opportunity to also showcase how policymakers and researchers and end users can work together, to make these as effective as they can be.”

Associate Professor Theresa Dicke says she and her team are grateful to all of the principals who’ve been participating in the survey and sharing their data, insights and perspectives. “We fully acknowledge that there’s a large research burden on school principals and teachers, and yet they are committed in supporting us,” she says.

Based on their findings, researchers from the IPPE are keen to continue developing a holistic model of school wellbeing, which implies that more autonomy, supportive environments and less controlling environments will predict the positive school climate, which in turn predicts the wellbeing, engagement and retention of school leaders, teachers and students.

Dicke says while her team are talking to principals, to peak bodies, and to policymakers – none of them are talking to each other.

“So everybody’s talking to somebody else, but what we really need is almost like a huge table where everybody is talking to each other at the same time,” she floats.

“We need evidence-based research and an impact, so end users and peak bodies would represent that, [and] program or intervention or policy, which is where the policymakers come in, to tackle the problems at the organisational and personal level.”

And while much policy is focused on school wellbeing, which is hugely important and commendable, she says a closer inspection shows that it is almost always focused on student wellbeing, while teachers and principals are the ones carrying the responsibilities to implement and carry out these interventions.

“And that’s just an added demand for already strained educators,” Dicke says.

“So not just is the health and wellbeing for educators important in itself, but also obviously, if you want to implement and conduct any measures for student wellbeing, this can only be sustainably and effectively done by healthy principals and teachers.”

Dicke uses the example of the National Teacher Workforce Action Plan, which while she says is great, is focused only on teachers.

We have to look at schools as systems, she says.

“So everybody in the school makes up a part of a system, and when you change the wellbeing or performance in one group, this will affect the others.

“Our own research, for example, shows that job satisfaction of school principals and teachers is positively related – so if one goes up, the other goes up, and vice versa.

“And in turn, the job satisfaction of our educators is related to student outcomes, including achievement, but also wellbeing.

“And so I feel like we when we bring everybody to the table, while any intervention for teachers or principals or students is important, we still need to take them into account together and see that we don’t just target one of these levels, but need to take into account all of the other ones and anything else that we need to change.”

To view the report on the survey, click here.